14th Century Clothing: A Few Examples from the V&A

The folks over at Historical Textiles posted a few images they took at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London:

I'm looking primarily for examples of fashion garments, not armor, and trying to answer the same few questions:

https://historicaltextiles.org/va-london/I want to talk about these pieces because they have some interesting examples of 14th century clothing which are relevant to my ongoing quest: how long should the doublet be? I hadn't really looked at these pieces before.

I'm looking primarily for examples of fashion garments, not armor, and trying to answer the same few questions:

- Are people wearing cotehardies (tighter, buttons), houppelandes (looser, fancy sleeves), or both?

- How long are the skirts on cotehardies and houppelandes?

- What information about hood styles can be determined?

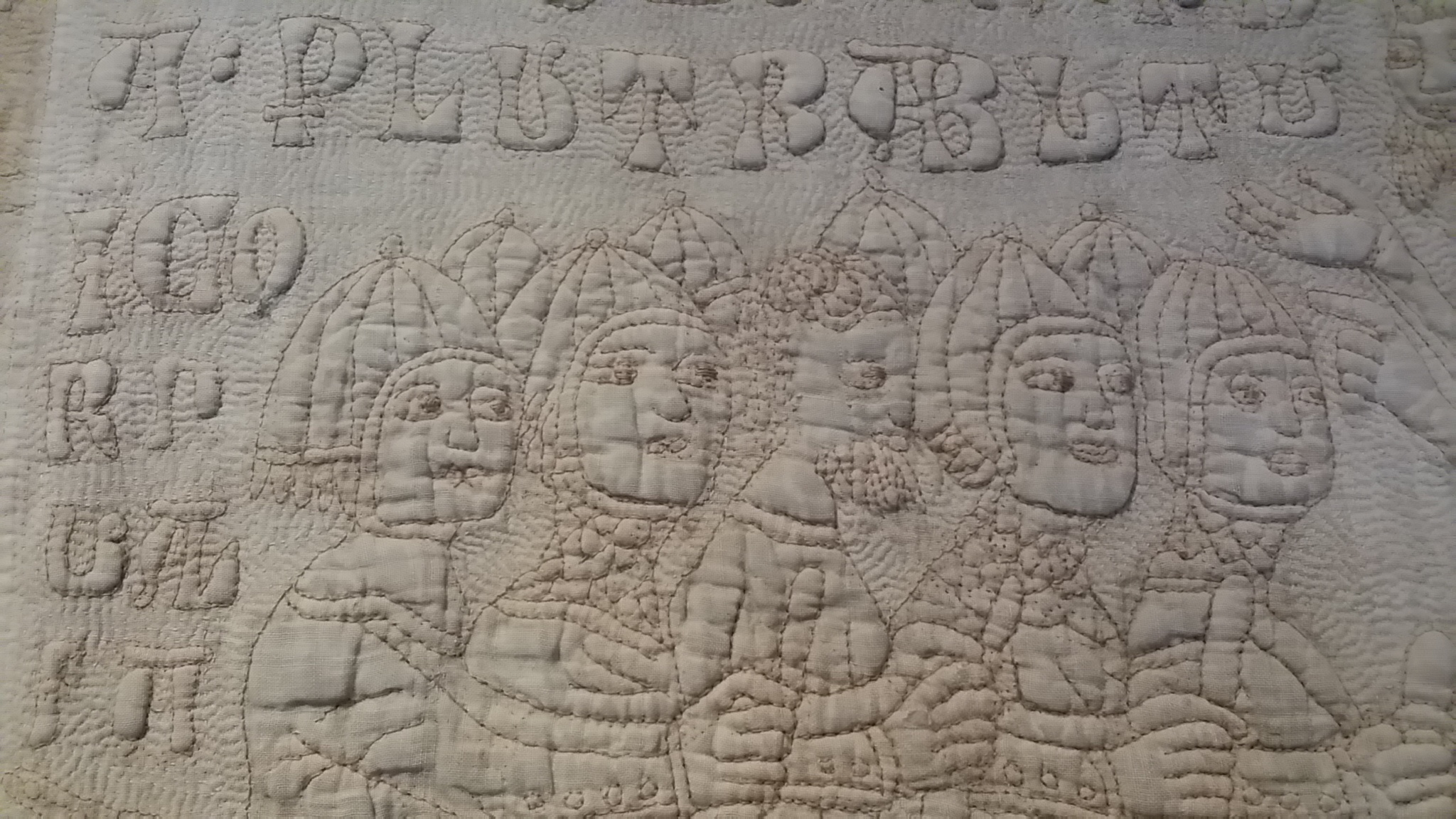

The Tristan Quilt

The first item is the Tristan Quilt, which dates to the second half of the 14th century, and was made in Sicily. The V&A's page for it has some good images, which I will link, and look at in the scene order listed on Wikipedia. I'd include the images, but V&A claim [1] to place a bunch of restrictions on usage, so I'll just link them to you. The images on the main V&A page are not in the same order as the chronology. If the links are broken in the future, blame the V&A for hating freedom.

The first description sentence with the link is from Wikipedia.

4 A page with a saddled horse. The page may be armored here. The outer layer of the page is a patterned garment with tight buttoned sleeves typical of a cotehardie, but on the chest, the buttons only go to the breast, which is more typical of houppelandes. This garment is likely a pourpoint, given its dramatic outline, and presence in the context of armor. The sleeves appear to be slightly baggy on the upper arm, perhaps indicating the armor beneath, or perhaps indicating a transitional style similar to what we saw in the Hours of Philip the Bold. The skirt is tight to the hips, and extends to just below the butt. There seems to be a line or two of decoration on the bottom of the skirt, and perhaps lacing holes for hose, or perhaps just roundel ornaments. Unusually, he's not wearing a hip belt like many other images are. His collar and cuffs are simple, perhaps just a binding.

7 Mark of Cornwall receives a letter from two kneeling ambassadors while Tristan stands behind them. The King wears a similar garment to the page in 4 - again, probably a pourpoint - although this time, the pattern is more complex, with the neck hole much wider across the shoulders, and a different fabric covering much of the upper chest and shoulders. In the context of 10, below, I think this is a hood or mantle. The king is seated, and his skirt does not cover his butt, unlike the seated people in the Hours of Philip the Bold. The two ambassadors have tight, buttoned sleeves suggestive of cotehardies or pourpoints, but the details are obscured by their mantles.

8 The ambassadors, in a ship rowed by soldiers and bearing a fleur-de-lis banner. The rowing soldiers show the same tight lower arm sleeves with buttons as we've seen in other images.

9 A ship, bearing fleur-de-lis banners with a man blowing a boatswain's call in the poop deck. Soldiers are similar to 8. The man with the whistle is depicted with a possibly-close-fit upper garment, but no buttons on the collar, leaving questions on how it fit over his head. He also has a silly hat.

The first description sentence with the link is from Wikipedia.

4 A page with a saddled horse. The page may be armored here. The outer layer of the page is a patterned garment with tight buttoned sleeves typical of a cotehardie, but on the chest, the buttons only go to the breast, which is more typical of houppelandes. This garment is likely a pourpoint, given its dramatic outline, and presence in the context of armor. The sleeves appear to be slightly baggy on the upper arm, perhaps indicating the armor beneath, or perhaps indicating a transitional style similar to what we saw in the Hours of Philip the Bold. The skirt is tight to the hips, and extends to just below the butt. There seems to be a line or two of decoration on the bottom of the skirt, and perhaps lacing holes for hose, or perhaps just roundel ornaments. Unusually, he's not wearing a hip belt like many other images are. His collar and cuffs are simple, perhaps just a binding.

7 Mark of Cornwall receives a letter from two kneeling ambassadors while Tristan stands behind them. The King wears a similar garment to the page in 4 - again, probably a pourpoint - although this time, the pattern is more complex, with the neck hole much wider across the shoulders, and a different fabric covering much of the upper chest and shoulders. In the context of 10, below, I think this is a hood or mantle. The king is seated, and his skirt does not cover his butt, unlike the seated people in the Hours of Philip the Bold. The two ambassadors have tight, buttoned sleeves suggestive of cotehardies or pourpoints, but the details are obscured by their mantles.

|

| Image by Wikimedia user Mabalu |

8 The ambassadors, in a ship rowed by soldiers and bearing a fleur-de-lis banner. The rowing soldiers show the same tight lower arm sleeves with buttons as we've seen in other images.

|

| Image by Wikimedia user Mabalu |

9 A ship, bearing fleur-de-lis banners with a man blowing a boatswain's call in the poop deck. Soldiers are similar to 8. The man with the whistle is depicted with a possibly-close-fit upper garment, but no buttons on the collar, leaving questions on how it fit over his head. He also has a silly hat.

10 Tristan giving his glove to Morholt. Obviously, the armor should be a caveat for the interpretation, but Tristan is wearing a pourpoint or something of that sort over it, and it goes down to just cover the groin. Note also the buttons from the elbow down, and apparently the different fabric on the lower sleeves, and the area (facing?) around the neck, as well as the wide neck holes. But this could be an armored fashion. Particularly intriguing is the row of circles starting beneath the patterned band on Tristan's upper chest. Are those buttons? If that's the case, maybe Tristan is wearing a hood or mantle, and since this is depicted very similarly to the king in 7, it's likely that he is too.

11 A Cornish noble paying money to seven of Morholt's men. The armored men again have pourpoint-like garments coming to just below the butt. Interestingly, the noble is wearing his hood as a hat. The part sticking out to his left, which would be the mantle of the hood, has lines on it, which may represent just the incidental folding, but could also be pleats or dags.

12 A ship bearing a fleur-de-lis banner with Morholt in the poop deck with a man blowing a boatswain's call. Similar rowers, one with chest buttons on at least the upper portion of his chest. The man with the whistle also has buttons down at least part of his chest, and an interesting striped fabric on his garment, which is similar to the other pourpoint-like garments we've seen in this quilt.

11 A Cornish noble paying money to seven of Morholt's men. The armored men again have pourpoint-like garments coming to just below the butt. Interestingly, the noble is wearing his hood as a hat. The part sticking out to his left, which would be the mantle of the hood, has lines on it, which may represent just the incidental folding, but could also be pleats or dags.

12 A ship bearing a fleur-de-lis banner with Morholt in the poop deck with a man blowing a boatswain's call. Similar rowers, one with chest buttons on at least the upper portion of his chest. The man with the whistle also has buttons down at least part of his chest, and an interesting striped fabric on his garment, which is similar to the other pourpoint-like garments we've seen in this quilt.

13 King Languis, with three nobles behind him, gives a letter to two kneeling ambassadors, while Morholt stands behind them. The three nobles all have garments in the same idiom we've been dealing with, with buttoned lower sleeves, skirts to just cover the butt, and simple collars. The king is similar to the king in 7, but has a belt. Tristan is wearing a pourpoint with buttons all the way down, and a hood, with a hip belt with very large floral plaques.

14 Morholt, with a mace, with a herald blowing a trumpet. These garments continue to be similar to what we've seen: buttoned sleeves, buttons all the way down (on Morholt), and hoods or mantles.

This quilt paints a pretty consistent image of pourpoints, with skirts to just cover the butt, and tightly-buttoned sleeves, but not necessarily with buttoned chests.

Another angle we can look at is colors, since we have so many men of similar costume.

The black is interesting since the 14th century marked the beginning of the rise of black as a fashionable color.

The Medieval Tailor's Assistant draws a very strong distinction between a form-fitting inner garment ("doublet") and a cotehardie, even though the only distinction I can figure from their book is that the doublet has the lacing holes for the hose, and is more consistently long sleeved. More importantly, it seems that most other people don't make this distinction - I've tried to drop it in this analysis. Besides, we don't really get to see much of an inner layer in these manuscript depictions.

They also have directions for constructing short-skirted houppelandes from a fitted block which I think was the image and timeline - late fourteenth century - that I had in my mind when I was looking for examples. While the pattern is slightly more roomy at the waist, it still winds up producing a lot of the same fitted silhouette that a cotehardie with open or bag sleeves would create - so perhaps that's what I should make for an outer garment, and target this specific transitional style.

[1] I'm fairly confident that, in the US, faithful reproductions of public domain works are not copyrightable, which these are, but I'm not interested in dealing with that mess for this article.

14 Morholt, with a mace, with a herald blowing a trumpet. These garments continue to be similar to what we've seen: buttoned sleeves, buttons all the way down (on Morholt), and hoods or mantles.

|

| Image by Wikimedia user JPS68 |

This quilt paints a pretty consistent image of pourpoints, with skirts to just cover the butt, and tightly-buttoned sleeves, but not necessarily with buttoned chests.

The Tristan Hanging

This is an applique wool hanging from the last quarter of the 14th century, in northern Germany.

The figures in the work are not particularly distinct, so I'll just describe the first 9 scenes to give you an idea:

Neither the V&A nor Wikipedia provide a list of the 22 scenes, so I will simply link the images as before without labeling them, in the order they are on the V&A's website at the time of writing. Their digitization is sometimes without color: many of the scenes can be seen in color in this larger image. It's clear from the colored image that many of the men are wearing hose of differing colors on each leg.

1 We see a pourpoint, with hip belt and plaques, not quite covering the butt because the wearer is seated. He seems to be wearing a hood (it's red). Are those buttons, or dirt spots on his chest?

2 The dragon slayer is wearing a sleeveless pourpoint.

3 another similar dragon slaying.

4 We see two similar pourpoints, while the standing man is wearing something a little different. It has less of a silhouette, and the skirt is longer, with lines on it. Are those more panels? But there's a man with a similar sleeve, so perhaps this is just piecing of the applique and not intended to communicate something unusual about the outfits.

5 Similar pourpoints, this king wears a hip belt.

6 The man on the left has clear buttons down the front.

7 Two more similar figures, with one of them also having clear buttons.

8 More similar pourpoints and hose.

9 Another pourpoint.

There are two men in the top row of the color image (missing heads) who are wearing something other than a pourpoint. One wears a blue coat with more volume, and one wears a robe or mantle.

There is also a man in the far bottom right wearing what looks to be a black houppelande, with very large sleeves, and a raised collar, along with a different hat (perhaps a bag hat?). He's talking to a woman with a similar outfit in green.

Another angle we can look at is colors, since we have so many men of similar costume.

Pourpoints / Cotehardies

Including sleeveless versions.

- Blue - 10

- Yellow - 2

- Red - 3

- Brown - 3

- Green - 2

- Black - 4

Hose

Counting individual legs.

- Black - 16, including a number of cases with both leg in black.

- Yellow - 8

- Red - 11

- Blue - 12

These interpretations are subjective, and I'm not sure if the authors meant to use color to indicate characters or something else - blue could well be Tristan, who shows up a lot.

The black is interesting since the 14th century marked the beginning of the rise of black as a fashionable color.

More Thoughts on Houppelandes, Cotehardies, and Doublets

The discussion thread on my previous article's G+ post contained some interesting discussion on what is and isn't a houppelande vs a cotehardie. I have to admit that I have a bad habit of imprinting on the first source that seems authoritative, and I think that's what happened here, a little.The Medieval Tailor's Assistant draws a very strong distinction between a form-fitting inner garment ("doublet") and a cotehardie, even though the only distinction I can figure from their book is that the doublet has the lacing holes for the hose, and is more consistently long sleeved. More importantly, it seems that most other people don't make this distinction - I've tried to drop it in this analysis. Besides, we don't really get to see much of an inner layer in these manuscript depictions.

They also have directions for constructing short-skirted houppelandes from a fitted block which I think was the image and timeline - late fourteenth century - that I had in my mind when I was looking for examples. While the pattern is slightly more roomy at the waist, it still winds up producing a lot of the same fitted silhouette that a cotehardie with open or bag sleeves would create - so perhaps that's what I should make for an outer garment, and target this specific transitional style.

[1] I'm fairly confident that, in the US, faithful reproductions of public domain works are not copyrightable, which these are, but I'm not interested in dealing with that mess for this article.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

But note that the images are public domain, as they are faithful reproductions of a work in the public domain.

Comments

Post a Comment